Little night stalker has a reputation worse than its bite

You’ve met this spider before. I say that with great confidence. Members of the genus Cheiracanthium are found worldwide and, far from being reclusive, are often out and about. We encounter two species: C. inclusum (native to the Americas) and C. mildei (a sneaky import). You find the yellow sac spider in houses and in foliage, prowling and patrolling, hunting for food. When it’s resting in a house during the day, it’s likely to be snoozing in an elongated sleeping sac tucked into a corner where a wall meets the ceiling, or two walls meet. That’s the “sac” part of the common name. It also favors rolled-up leaves and ground debris, like bark.

The yellow is variable: it can be golden, brownish, lemony, or even greenish. In our place we call it the “glow in the dark spider” not because it has such a superpower but because the lemon chiffon color reminds us of toys or stickers that shine when the lights go out. And because it’s a creature of the night.

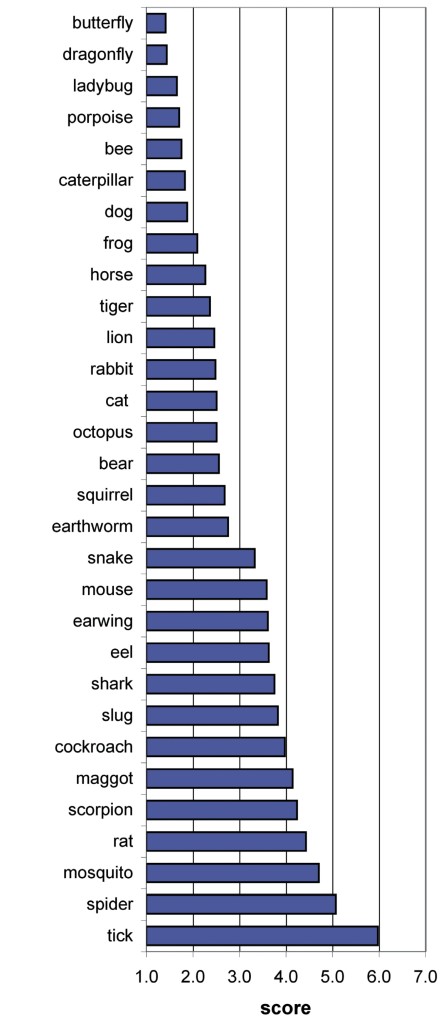

Cheiracanthium is worth talking about not only because it’s widely encountered but because it has a reputation. It can bite people, and does—but of course spider panic kicks in when people learn of this fact, and the yellow sac spider gets saddled with all those ghastly rumors about unhealing sores and swelling, with gross overkill pictures delivered by Dr. Internet. In truth, the bites start with a sting and turn into redness and itching. That’s pretty much it, not that it sounds like fun.

Can’t a pest just be a pest? That’s not just my assessment, by the way. That’s the word the viniculture people apply to the Cheiracanthium spiders that loiter in the vineyards and fields of my fair state, stickying up the vines with their silken retreats and occasionally nipping fieldhands. Actually, it’s a pest that eats other pests, which is considered a plus if you’re trying to cut down on the agricultural pesticides.

I bet a lot of those spiders end up in the crush come harvest time. But c’mon, you asked for organic! It wouldn’t be the first exotic undertone in your fancy, fancy yellow wine.

This is a spider that’s maybe harder to love than others. But hear me out.

The estimable Spider Club of Southern Africa, my chums in the Southern Hemisphere, posted not long ago on their Facebook page: “The sac spider, yellow sac spider or house sac spider, has been declared ‘not guilty’!” What was the alleged crime? Necrotic wounds. Cheiracanthium spiders in South Africa had been accused, on disputed evidence, of causing the same kind of serious sores of which brown recluses are capable. More:

The media got hold of this research, it was repeated many times in both scientific and popular literature without rigorous investigation and a legend was born. Recent research, however, has concluded that their venom does not contain the compound that causes necrosis and that this reputation is undeserved. House sac spiders are no more or less dangerous to humans than any other spider and like all spiders they try their best to avoid contact with us. (Dangerous Spiders in South Africa, by Astri Leroy, revised 2015)

Envenomation is a complex phenomenon. To some wildlife experts in South Africa, for instance, Cheiracanthium is still not in the clear. The African Snake Bite Institute expresses a cautious view that the local species, C. furculatum, might indeed cause serious problems, although it concedes most bites are still little more than nuisances. Some components of its venom call for further study. Among other variables, the institute says that “scratching may introduce bacteria from the hands/nails of the victim to the wound.” And it’s undisputed that these bites tend to be itchy.

Let’s pause there for a moment. The yellow sac spider doesn’t stand in the dock alone. There’s broad research trying to pin down whether, and when, an otherwise insignificant spider bite might cause health problems simply by breaking the skin. Necrotic wounds and the bacterial skin infection known as cellulitis, for instance: those are very likely to be caused by staph bacteria, which live on normal human skin and in the environment. And what can break the skin? Anything pointy or scrape-y. Not just invertebrate mouthparts but spines, thorns, nettles, wood splinters, rusty tools, dog toenails, dirty fingernails.

So why is a skin wound from unknown causes instantly called a “spider bite” anyway? Too often, even experienced medical personnel will shrug that it’s a spider bite because it looks like a spider bite. Notice how very often the news articles claiming to report on a ghastly spider bite add, “The victim never actually saw the spider that bit him.” Both of these statements are beliefs, not evidence-based conclusions. That’s why experts have a general rule that if a spider was not seen in the act of biting, and then identified by a spider expert, it’s unwarranted to call something a spider bite. And you really don’t want to call something a “brown recluse bite” if you live thousands of miles away from any and all brown recluses. But oh, people do.

And it’s not just idle chatter. Crying “spider bite” is a potentially dangerous tic if it leads a doctor down a blind alley trying to fight a nonexistent venom when he or she should be fighting an infection. And it sows confusion if it makes everyone in your social media circle afraid of something that doesn’t happen. (Yes, fifty million British tabloid readers can be wrong.) As I’ve mentioned before, arachnophobia can kill: consider the person in the car you smash into while flailing around at a harmless spider, or the burn victims who tried to KILL IT WITH FIRE.

And don’t forget stress. If you spend your life in fear of small animals that are always part of your environment, that just has to shorten your life, not kidding.

Yellow sac spiders may not be cuddly, but that’s no reason to make them monsters. Sober scientific folks are still looking into cases of envenomation of our sallow friend, but the evidence on balance is that bites, when they happen at all, are a nuisance.

Speaking of nuisances, these vagabonds do clog up certain vital parts of cars with their sticky little webs. Cars are a great place to lay low during the day. No worries, this too shall pass. Soon we’ll all be driving electric Futuremobiles without a lot of important hoses and tubes under the hood. But there still might be a glow-in-the-dark spider roaming your electric car’s glowing dashboard. Just wave as it goes by.