Ladies of the night

The widow tends her parlor.

I don’t worry about the widows. They’ll be fine. Putting aside the question of whether I should be worrying about them, I know they’re a resourceful bunch. Ever since the first bulbous lady of the night appeared along the property-line fence, spinning her tough, ratty web as I walked past with the flashlight on garbage night, the black widows have endured. Now that the builders next door are about to demolish the fence and build a new one, it’s very likely that the widows will just colonize that one, too. I won’t bring it up with the new neighbors, at least not right away. They’ll think my sympathies are misplaced.

The widows who haunt the fence haven’t been there long. When we bought the house 11 years ago most of the spiders in the nooks and crannies of the yard were Steatoda grossa, false black widows. They scare the unwary, because they’re petite, dark-chocolate replicas of the widows and they hang out where you’d expect a widow to be. After a little research and a lot of familiarity I saw them as chums, and now salute the false widows as they fumble away from the broom. But then Latrodectus appeared—not actually glistening in the light of the full moon, though that enhances my mental picture—and suddenly Steatoda grew scarce. This new species bore watching.

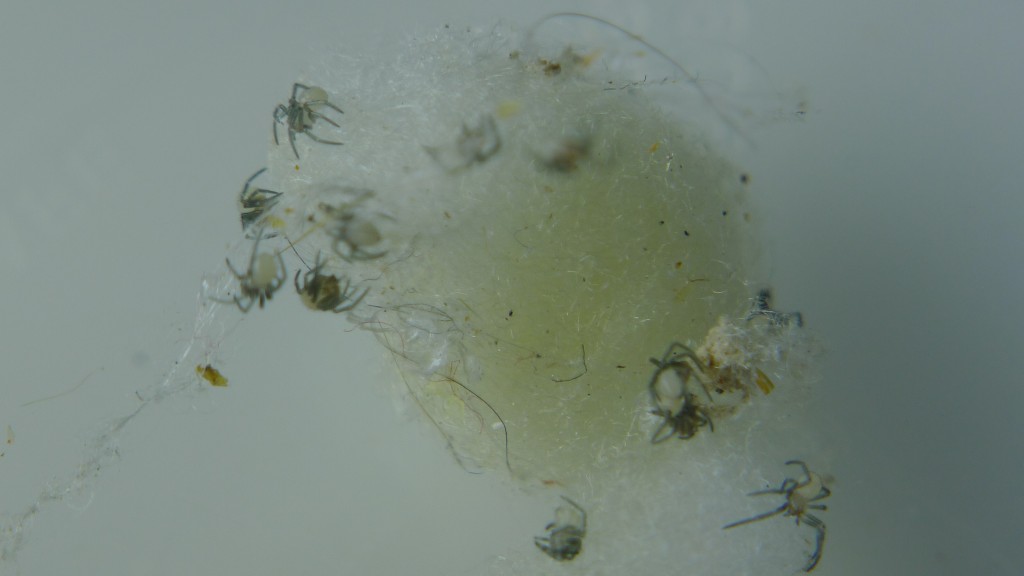

I thought about wiping them all out before they got too entrenched, but never had the heart. I caught and relocated a few. I kept a couple others in terraria out of curiosity, but when they spun egg sacs I questioned the wisdom of the project and relocated them, too. And now they’re part of the landscape: invisible by day, out on their lines by night, always ready to scoot back into a downspout or between the slats if they detect something amiss.

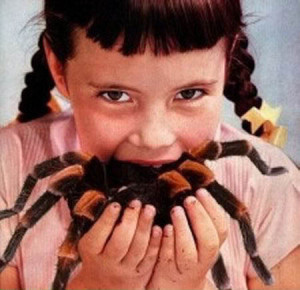

And that’s why, I think, I let them be. The western black widow and her more notorious Theridiid relatives are nothing to mess with. I won’t dandle them or coo at them. But nor are they coming to get me and my children. Having tried many times to catch them, I tell you it’s not easy: they’re wary and will retreat from the slightest suspicious vibration. Even if I plowed through their triplines while taking out the trash, they wouldn’t charge me; rather, they’d do their clumsy best to sprint back to safety. It would take me jamming a finger into their lair or picking one up with my bare hands to get bitten.

By now, the widows are like neighbors. The ones who don’t keep up their yard, whose taste in Christmas decorations runs to the tacky, who got the F-150 on blocks in the driveway, sit on the porch in the evenings, don’t make eye contact. They probably keep a handgun in the nightstand. It’s enough to know their name; no need to be overfriendly. Still—it’s their neighborhood, too. If they go away of their own accord I’ll be relieved, but in the meantime I don’t feel threatened.

The black widow is a medically significant spider, no doubt. The human body’s response to her neurotoxic venom is called latrodectism, something I don’t want to experience. (You know you’re famous when somebody names a whole disease after you: benign Linsanity, deadly Snookiism.) Latrodectism is an agony of clenching muscle pains, often with nausea, headache, copious sweating, and accelerated heartbeat. Medical sources repeat like a mantra: death is rare, although risks are higher for children, the elderly, and people with compromised cardiovascular systems. Antivenin works but usually isn’t necessary, and it can make things worse.

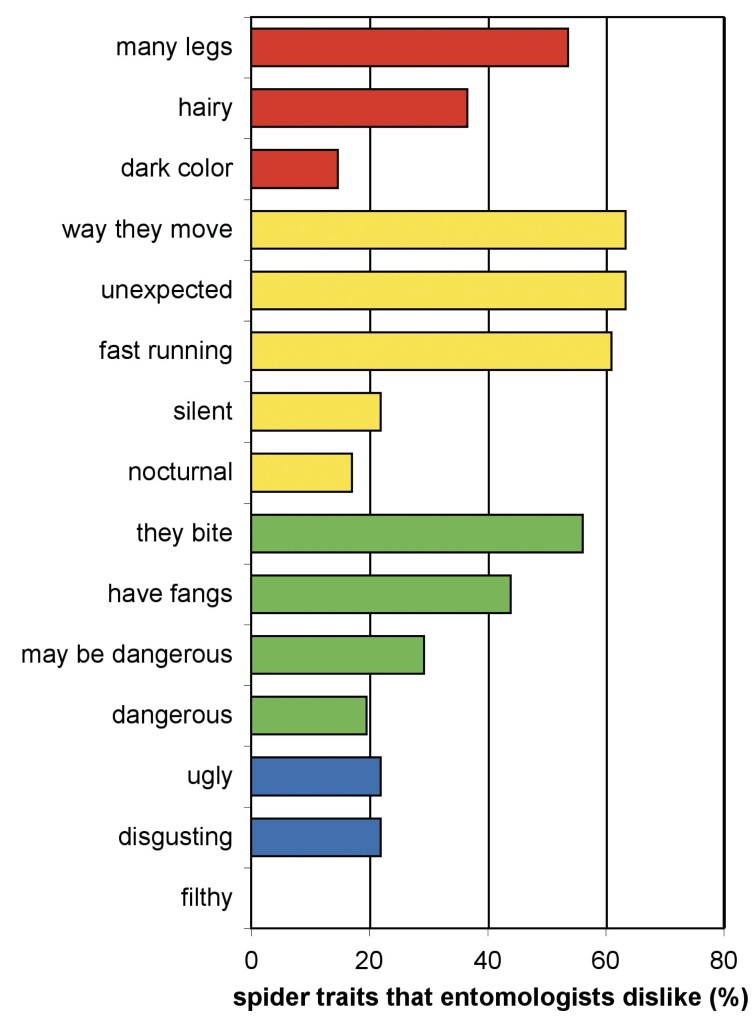

The widow isn’t “lethal,” forget what the Internet says. I sought a hard number for this, not the moldering Netlore people toss back and forth. Here: the latest report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCS) tallied 2,168 widow spider bites in the US in a year. No one died from them. Even if you added in the 3,345 “unknown spider/insect” bites (including my pal the Invisible Spider and anything else that crawls, visibly or not, across the national epidermis) … still zero deaths. Only 13 widow cases were even considered major. The largest category of outcome: “minor.”

Now, there is that “Case 1259,” the middle-aged asthmatic hospitalized for a black widow bite. Thirty-six hours later, he’s dead—but of anaphylactic shock. Triggered by the antivenin itself, not the bite.

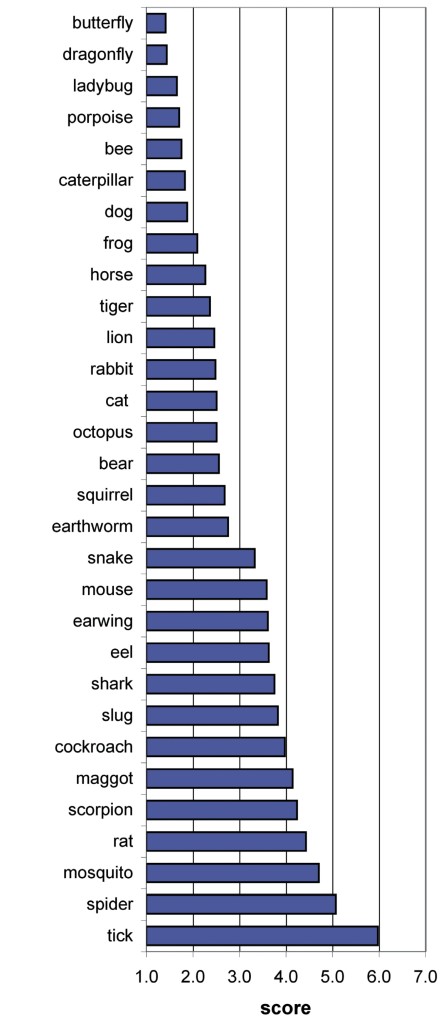

Bee/hornet/wasp stings were three times as numerous as spider bites—with two fatalities. Other villains:

- Car antifreeze, seven deaths

- Toilet-bowl cleaners, three

- Hearing-aid batteries, two

- Liquid laundry detergent, two

- Good ol’ “ethanol (beverages),” a raucous twenty-one.

(Interestingly, the report cites a single death from “other spider bites and/or envenomations,” but since widows, recluses, and Invisible Spiders were already tallied separately, it’s a mystery. Perhaps it’s the unfortunate Case 1259.)

Another report, from 2005, explored animal dangers to humans and calculated an average of six deaths from venomous spider bites every year in the United States. Curiously, it found almost as many deaths from “non-venomous arthropods,” and cited the anaphylaxis risk. And note: in this telling, hornets, bees, wasps, and ants were nine times as dangerous as spiders. (Curiouser still, isn’t it, how the AAPCS hasn’t found even one widow fatality since it began issuing annual reports in 1983?) Cows, horses, and mules go bad, too.

The widow’s reputation has clearly been besmirched. She isn’t always lethal even to her mate. It would make for a better episode of “Who the (Bleep) Did I Marry?” if she were, but the fact is lots of spiders are prone to husband-noshing, depending on hunger and other circumstances, and she’s not a standout.

The adult male widow is a skinny guy, with rather attractive marbling on his trim, brownish exoskeleton. (No one suspects him of being dangerous to humans, unlike his bride.) I see him lounging around the lady’s porch of an evening. Our widows get lots of gentleman callers.

And like another famous widow, Blanche DuBois, these femmes noires depend on the kindness of strangers. Me.