Why protect this endangered money spider? Here’s my two cents

This is just adorable. And if it reminds you of Monty Python, me too. If it were me, I’d title this campaign “Life of Brian (the Spider)” or perhaps “Ministry of Silly Walks (with Eight Legs).”

Buglife, which calls itself “the only organisation in Europe devoted to the conservation of all invertebrates,” is crowdfunding on behalf of the horrid ground weaver spider, Nothophantes horridus, whose English habitat is threatened by development.

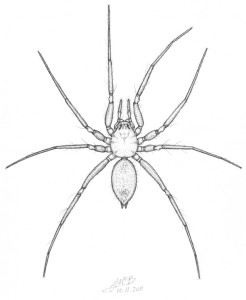

The horrid ground-weaver is so poor it can’t even afford color! Actually, it’s kind of brown. [Illustration © Fergus McBurney]

But even better! The little arachnid is of a type known as a money spider, a universally harmless breed with a friendly, colorful common name. Why do they call it a money spider? Because legend has it that seeing one, and protecting it, will bring you wealth and good fortune.

Because, you know, it will. Look at me: crawling with both spiders and gelt! “If you want to live and thrive, let a spider run alive” is a great old (also English) proverb that your crumpet-baking granny taught you when you were a sprat. The Oxford Dictionary of Proverbs, which should know, cites its use among Kentish grannies as far back as 1867, though everyone thinks it’s much older.

(In the UK, by the way, money spiders are converted to pounds sterling, thus making them “pound spiders.” No wonder they’re endangered.)

Buglife cheerfully points out that the spider isn’t horrid at all, unless you consider unshaven World Series players to be horrid:

The spider’s name comes from the fact that its body is rather bristly—the Latin origin for the word horrid [horridus] is bristly.

The conservation group worries that a planned housing development at an abandoned quarry in Plymouth will wipe out one of just three places where the tiny spider is known to live. Buglife conducted a petition campaign on the horrid spider’s behalf and is now crowdfunding for a proper scientific survey to find out its range and how to protect it with an emergency preservation plan. As of February 4, they’d raised £1,504 toward a goal of £9,600. The money spiders had better start shaking those trees.

Cool activism. Not just waving around picket signs or blocking traffic or chanting monotonous slogans, but putting time and money into concrete solutions. And on behalf of a small creature most people have never seen, and would probably squish if they did.

I’m weary of crowdfunding appeals; they’re either worthy but far too numerous, or flaky and self-aggrandizing. But this appeal for the horrid ground weaver is no hipster smirk, unlike the guy panhandling online for his mac-and-cheese recipe. Everyone knows biodiversity is good and that it suffers every day from our roads, buildings, conflicts, and other ways we use our landscape to eat, find shelter, and make money. A few bucks to protect this money spider is spare change, well spent.

UPDATE: Another day has passed, and the horrid spider fund has reached £2,654! That’s, like, ten kilometers! Good show, crowdfunders, for putting your money where your webs are.

SECOND UPDATE: They made it! “Team Spider” reached its fundraising goal and is proceeding to arrange the habitat survey. And how could I have overlooked the YouTube animation? “Not everyone likes spiders, but no one likes extinction” is a slogan to remember.