Hey, Cellar Spiders: I’m in Your Corner

I’ve figured out the problem with Quora, and maybe other Q&A sites. You can thank me later. The problem is Siri. And Alexa, and the Google Lady. Especially the Google Lady, because she’s so smart and so prompt, and I think she’s the best example of that “bray your question into the air and I will answer” phenomenon we’re all being sold.

So, the problem: people don’t read other people. In the dim days when the Internet was fresh and friendly, it was promoted as a place where knowledge accumulated, like a library. And like a library, it required that the initiate search for answers. It was a lot faster than a card catalog and a scuffed trestle table somewhere, but it still required an awareness that your question had been asked before—and likely answered.

You’ve seen it: the question posed on Facebook or Quora, and answered well or semi-well. And then someone new drops a post as if the first were invisible. Then that one is patiently fielded, and a link provided. Then more and more people stumble in, each one reacting only to the initial post and oblivious to the new ones. Or they start feeble side arguments. The informed posters keep offering the same answer, and get frustrated. In the end, only a couple of people get the news, while everybody else is just bottled up in some kind of Brownian motion of cluelessness: still asking, still reacting, shouting “Photoshopped!” even if they don’t know Adobe from a doobie, or “Fake news!” or “Trump!” as the bump into each other’s random views.

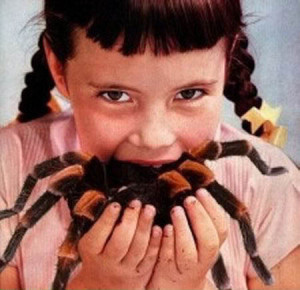

That brings me to spiders. There are spider-smart people out there, and smart curious people. Then there are the fools who feed the British tabloids, and the vast groups of people who sustain the most ridiculous myths about spiders, and the less ridiculous ones, and the whole silly corner of the online multiverse is sustained by one fact: people just won’t read the comments.

How many years will people ask “are daddy-long-legs spiders really deadly? But their fangs are too short to bite people?” I enjoy writing about the daddies, I really do. But the truth is out there. If folks took the time for a smidgen of research—just a couple of clicks, all I ask—we’d have time to tackle deeper or more mysterious things.

Here’s how I responded to this old chestnut on Quora just the other day. At least the questioner turned it into a “why” question. Like a lot of the better Quora questions, a little twist on the premise keeps it from being just a lazy schoolchild’s attempt to collect homework fodder. And I bet I’m ahead of the Google Lady this time. “Alexa: pat me on the back.”

“Alexa: Is it true this spider wouldn’t hurt a fly?” “No, it would definitely hurt a fly. But not you.”

Q. Why do so many people firmly believe a daddy long leg spider is very venomous?

A. Because the “deadly daddy” myth harmonizes so well with how urban legends are usually born. It’s . . .

Pleasantly counterintuitive: the stickiest urban legends always have an element of “wow—I didn’t know that!” You’ll never be able to launch an urban legend that rabid dogs are dangerous, or that Mister Rogers liked peanut butter. But if you can concoct a tall tale about how rabid dogs were responsible for the breeding off the Goldendoodle, or Fred Rogers is a former military sniper and current Satanist, you have an audience. People enjoy having their ears tickled.

In this case, the sweet counterintuitive fact is that daddy long-legs spiders (Pholcidae) are weak, spindly, shivery little things you could blow away with a gentle breath. So to learn that they’re actually military snipers, uh, deadly creatures, packs a powerful “Wow! Who knew?” That supercharges the legend.

Told to you by a friend: Think about all the times a vague, wacky story has come your way. Likely it was from a friend, relative, agreeable stranger, or favorite celeb. Jan Harold Brunvand, the godfather of the urban legend research, dubbed this the “FOAF” phenomenon: friend of a friend. The person telling the tall tale rarely claims to be the person it happened to; no, it was always “my girlfriend’s uncle,” or “my dad’s Army buddy,” or “a TV comedian recalling something he was told.” Removing the origin of the myth from the hearing of it insulates it from fact-checking. And since the original source is often unknown or forgotten or even dead, it makes debunking the tall tale impossible.

Whoever told you the daddy was deadly was likely a school chum, an acquaintance, or somebody who spends too much time on the Internet and too little time at the library. Maybe it was your mom, trying to get you to stop torturing poor helpless arachnids. Whoever it was, it was somebody you trusted—often for no good reason.

Ever-so-slightly plausible: Daddy long-legs spiders are venomous . . . but so are all other spiders, except for a few small groups. They do have little fangs (again, like all other spiders). Conceivably they could bite someone; after all, they bite bugs all the time. They might even kill a black widow now and then, and since widows are genuinely potentially harmful to people, doesn’t that mean that the cellar spider is actually even MORE of a boss?

A dash of cold water: the only investigation I’ve ever seen into the deadly daddies was on “Mythbusters,” in which Energizer-bunny Adam Savage burned up multiple screen minutes trying to get a box full of pholcids to bite him. In the end, he claimed that one had, yet all he got was a tiny red spot. But since he’s a ginger, I was never convinced he wasn’t just calling out a freckle.

And . . .

Spiders always have it hard. Most of what you know about spiders is wrong to begin with, so this libel against the frail and harmless pholcid is par for the course. Our parents or grandparents used to tell wild tales about the “deadly spider in the beehive hairdo” that killed girls of the “American Bandstand” generation. And during the Southwest decoration trend of a few decades ago, we all heard creepy tales of the “erupting cactus”: a plant brought in from the desert that started shaking and suddenly disgorging thousands of deadly baby tarantulas! And who could forget the breathless childhood stories about spider eggs in BubbleYum? Aaack! All lies, of course. But so thrilling.

Today, we pass around grisly pictures of open sores that are supposedly caused by brown recluse spiders, wounds that erupt thousands of miles from where any brown recluses actually live. Crypto-crazies head off to the wilds of Africa even now to hunt for mythical mystery spiders the size of golf carts. And panicky British schoolmarms shut down entire schools out of fear that a harmless invasive spider, the false widow, is going to run amok, snatching apple-cheeked pupils like something out of Harry Potter.

Face it, spiders are the go-to creature if you’re going to tell colorful lies. And the daddy long-legs spider is everywhere, just minding its business (and yes, making a bit of a mess), and always ready for its closeup.