Will these startups have legs?

No matter how you spin it, turning spider silk into a product is tough. For thousands of years people have understood that it has certain qualities humans can put to use, mostly based on how amazingly strong and light and tough it is. But nobody has ever created or engineered spider silk on a commercial scale, even in an age where technology blossoms as never before.

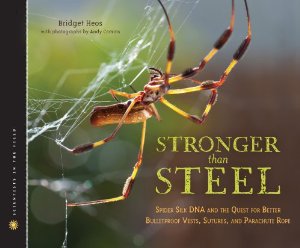

A fun book, aimed at younger readers, explores the quest to commercialize spider silk. Lots of cute goat pictures and modest Canadian optimism, eh.

Remember the goats? They’re still around, but the effort to cash in on “spider goats” is moribund, despite what Al Gore said at SXSW just a few months ago. Feta is easy, fiber is hard.

The simpler, lower-tech method of wrangling spiders—patiently unspooling them by hand, like so many little bobbins—is never going to go big. There’s just too much effort for too little product. And they kinda bite. I’d say the livestock were also too small, but that’s never seemed to inhibit the silkworm industry. No, the problem is output.

Then there’s Spiber, a name so goofy it’s being used twice: once by a Swedish research company and again by a Japanese startup. A contraction of “spider” and “fiber,” I’m sure, but I’d call myself Spfiber instead, or SPiB (pronounced “spibe”), or I don’t know. As long as a name’s going to sound wacky, go the whole wack. Both have cool futuristic websites, though the Japanese company has more of the coveted Steve Jobs “my future is your future, plus lots of white space” look.

Spiber of Japan is surging ahead in the business press because it says it’s almost ready to produce for real. It can already cook up a kilogram of spider silk protein a day, so the company says, which if I read right equals 29 million feet of synthetic silk thread. It hopes to produce far more as soon as 2015. The process uses “microbial fermentation,” which is rather elegantly vague. Both companies in fact hijack a bacterium, the notorious E. coli, to synthesize the protein that’s the basis of their silk.

QMONOS my house: This shimmering blue number is billed as the first garment ever made entirely from artificial spider silk. QMONOS is a shouty version of kumonosu, Japanese for spider web (“Here at Spiber, the only thing missing is ‘U’!”)

What to do with oceans of artificial cobwebs? The Japanese are talking lightweight car parts and have linked up with Kojima Industries, a Toyota partner. Both outfits mention medical technology such as scaffolds for culturing tissues, wound healing, and bone repair.

These products are apparently made without the need for the second part of the spider’s magical apparatus, the spinneret. Those little aimable, controllable spigots are how a spider takes liquid silk and tugs it into the miraculous chain of proteins. The lack of such a mechanical device has been the downfall of other spider-silk ventures in the past. The Spibers are cagey about how they get around this problem.

Have the Spibers got what it takes? A dorky name is only half the battle, even for true beliebers. Wait and see.