Come into my parlor, my pavuchky

If you were born in a barn, there were probably spiders nearby. I wonder if that’s the real reason for the folk tales about Christmas spiders. But in the legends these spiders aren’t hanging curtains for Baby Jesus, or weaving the swaddling clothes or making sure the manger is bug-free. Instead they’re scurrying around a family’s humble Christmas tree, admiring the ornaments and leaving behind silk strands as they do, and when the Christ child arrives to bless the home, he turns the cobwebs into silver and gold tinsel.

O Tannenbaum, O Tannenbaum, I don’t know the German word for “spider” . . . (pictured: festive decor from the Dusty Raven Gallery, www.etsy.com/shop/thedustyraven.)

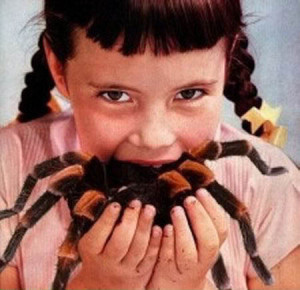

Wonderful! And it resonates with something I often discover when taking down the family tree. Spiders do live in them!

In our part of the country, cut Christmas trees come from the frosty Northwest. Somewhere along the way, maybe in the tree farm, our fir usually collects a small hitchhiker: a shiny, almost metallic jumping spider (Salticidae) with a taste for heights.

She or he is at the tip-top of the tree when I go to take it down after New Year’s. Why there? I don’t know. There’s no spider food nearby, unless you count stale popcorn and candy canes. But the spider is almost always there, sometimes snug inside the star itself, surveying the New Year with its sharp eyes. I set it free in our winter yard, wishing it luck, hoping it doesn’t miss its hipster Oregon friends too much.

I don’t know its species, if indeed we see the same kind every year. Salticids are the largest family of spiders, with some 5,000 named species. This particular elf could be completely new to science, who knows? Stranger things have happened at Christmas time, Ebenezer.

The Christmas spider legend is usually attributed to Ukraine, which has a tradition of hanging web- and spider-shaped ornaments (pavuchky, or little spiders) on the tree. Since I don’t have a Ukrainian babushka, I’d never heard the story. The tale involves an archetypal poor widow and her hungry children. A pine cone falls to the floor and grows into a fir tree, but come Christmas the family has no money for ornaments. They go to bed sorrowful, but in the night the household spiders clothe the tree in silk tinsel, the Christ child leaves swag, and the family is henceforth happy and prosperous.

The tale may have originated in Germany, where ancient tree worship sprouted into the modern Christmas tree tradition. But Ukraine has rich Yule and new year’s traditions of its own, as well as a tradition of revering spiders and depicting them in embroidery and weaving.

I learned that the Christmas tree in Ukraine accompanies an older symbol of the year’s end, the didukh, or sheaf of grain. “The spirits of the ancestors come into the home in the didukh for the holy days,” Orysia Paszczak Tracz writes in an article about Ukrainian traditions. “They had lived in the fields in the grain helping the bountiful harvest.”

That sounds just like my treetop spider. She comes indoors for a spell: a warm home, festivities, reflection, and rest. And then resumes, during serious winter, more serious pursuits.

So raise a toast to the well-intentioned, harmless house spider. She’s pals with Jesus and a dutiful housekeeper, in her own way. Look for silken strands amidst the gold.