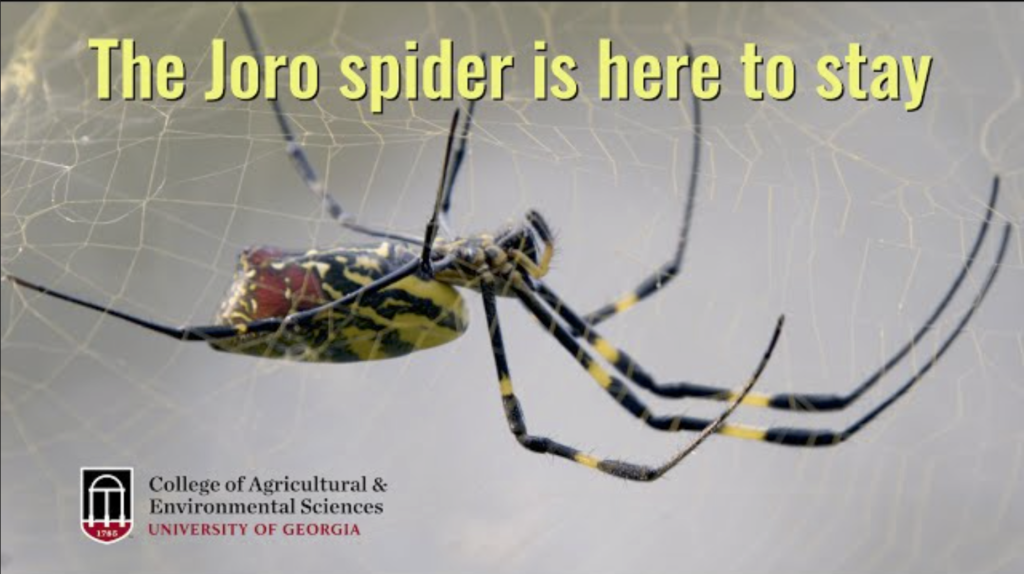

Big, colorful spider is fiery, but mostly peaceful.

The joro spider (Trichonephila clavata) has landed! Or so say the news reports of the past few weeks. Like most spider announcements, this one is a combination of fact, wonder, fear, and utter spew.

Is it big? Yes, kinda, though not on a tarantula scale. Is it eye-catching? Oh yes; it looks like a bunch of party balloons got married. Is it spreading? So it seems, since this Asian orb weaver likes living in the US and has been established in the hospitable South for a while—principally Georgia, so you know Florida Man will be running into it soon enough—and is poised to stretch its legs, legs, legs up along the Eastern Seaboard. A related big species, T. clavipes, has been in the Americas all along yet nobody’s panicking.

But does it jump? Or “parachute”? Well, no . . . I think we all have too much military invasion on the brain these days. Giant joro spiders do not plummet from the sky. Like many other species of spiders, their young (emphasis: tiny, tiny young) will disperse after hatching by releasing silk into the air and “ballooning.” This is a magical process that scientists are learning more about all the time, since it employs a hidden mechanism that’s not nearly as straightforward as “point your butt at the sky and hope for a breeze.” Read up on it if you’re a science geek, and marvel.

If you’re just an arachnophobe, be still your beating heart. If a juvenile joro wafts into your garden, you won’t even notice it. If it grows up there and gets to work on its typically large web, you will.

And here in California, we’ll just have to look at pictures on the Internet. Hi, joro! There’s no sign of the big guys and gals here.

Oh, and the name? From Japanese mythology. Here’s the definitive rundown. The beautiful spider-woman (not the kind that kisses? I guess) can scare you or thrill you, or reel you in with her silk, or have you for dinner. She sounds nice.

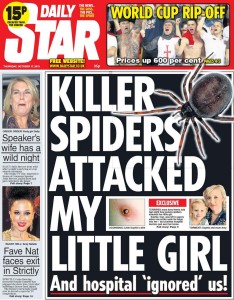

I don’t know whether the US news media are getting better at spider stories—at least some of them—or whether the tide of joro panic has yet to hit. Most of the reporting has been fairly factual. Headline writers have been tempted to screech, but for the most part they’ve been somewhat subdued. “Harmless but scary” may be the best we can hope for in terms of information, and yeah, that’s sort of like “fiery but mostly peaceful,” but if the alternative is the typical UK-style hyperventilation, I call that progress.

I’ve noticed this on social media, too. A neighborhood group I weigh in on has been inching forward on spider postings, so that at least one or two stolid, fact-based neighbors are sure to comment when a photo is put up for identification, or someone recalls a grisly medical event he blamed (with no evidence) on a spider that was never seen and doesn’t live around here anyway. There’s still the comment chorus (if they were a band, they’d be called The Monotones) who post KILL IT WITH FIRE or BURN DOWN THE HOUSE or a handful of other moldy responses that my savvier neighbors warn are sometimes actually taken seriously. When panic meets fire, hilarity does not ensue.

If giant spiders are not invading the homeland, there is one point on which “invasion” is the word of the day. These spiders don’t belong in the United States. Many, many species are here without permission, not just arachnids but reptiles, insects, birds, plants . . . and the Southern states are often where these species set up a base for expansion. Even in my city, most of the common spiders I see are non-native species and seem to have crowded out the natives. You’d think that a black widow (Latrodectus hesperus) would be able to hold its own in the soft suburbs, but maybe not. Creatures that frighten suburbanites aren’t always much of a threat to a rival small animal that’s managed to unlock the secret of being Baddest of the Backyard. In Southern California, for instance, in many places the brown widow (Latrodectus geometricus) is pushing out the black widow. How? What’s the secret sauce?

Steatoda nobilis, a false widow spider that doesn’t belong here, is abundant in my spider-hunting spots. Five years ago, I saw none. Steatoda grossa was queen, and L. hesperus lurked around the edges. Now those latter two species appear to have shipped out. S. grossa might have gone back to Hollywood to try to rekindle its movie career, but I think that with the universal acceptance of computer graphics, that ship has sailed.

The joro spiders’ impact on their new homeland is still unknown. They might be beneficial in some ways, such as eating mosquitoes or agricultural pests, or their presence might tip the ecological balance the wrong direction like those monitors and fat pythons lounging around Florida . . . or it might be a wash. Every invasive species is a variable, and nobody can solve the equation with any certainty.

But what’s certain is that joro spiders aren’t going to hurt you, or your pets. And since they move slowly (been in Georgia since 2014, haven’t moved much since), you still have plenty of time to get that arachnophobia taken care of. Therapy is cheaper than a new house. Especially in California.