Man in black

Three times in a year this audacious spider—hey, that’s its actual common name, the audacious jumping spider—has leaped into my life. Not the same actual spider, but different individuals of the species Phidippus audax in different places.

One even posed for some surprisingly good (if fuzzy) close-ups in which it appeared to have been preening its handsome, hairy self in the reflection of my iPhone.

I don’t remember ever seeing this species until a year ago, despite a lifetime spent in its range. Then, last summer, my daughter was planting trees and texted me a blurry snap of a spider her fellow planters thought was worrisome. It was loitering on a tree trunk with a grasshopper it had caught. A quick check with Professor Internet suggested Phidippus audax, and I told her there was nothing to be concerned about, unless you were a grasshopper. That’s me, spider tech support.

And then there was the children’s section of this precious twee earthy gift shop we were visiting in Costa Mesa a few weeks ago. The specimen you see in my photos was hanging out amid some pastel-colored little frocks, as I recall. Bold, indeed! Borderline pervy. Resisting my efforts to catch it on an envelope, it sidled into a box holding a hot-chocolate mug. Thankfully, no haters were about, nor fierce warrior moms. When I tipped the spider out of the box, it hung on with a dragline, giving me time to walk it to the door and let it land in the bushes. The clerks said they appreciated my green gesture, though they kept their distance and emitted faint screams.

A mere day later, my daughter and I were touring the restored wetlands at Bolsa Chica Beach, feeling fine to see how nice were the marshes and chaparral at what my family used to call Tin Can Beach. At the visitor center, housed in a biggish trailer, we saw the usual pickled and stuffed marine specimens and blowsy dioramas you’d expect at a site where the budget all goes to land acquisition, not fancy displays. But lo: in the corner of a plastic terrarium, a huddled black blob that looked strangely familiar. The young docents didn’t know what it was.

My cue! Out came the phone, I called up these photos, and asked, “Does it look like … THIS?” And how much better does it get than having a big, clear picture of the very jumping spider in question, right there at the ready? It doesn’t. It was like that scene in “Annie Hall” where Woody Allen drags Marshall McLuhan out from behind a potted plant to explain a Marshall McLuhan concept. Now the audacity was all mine.

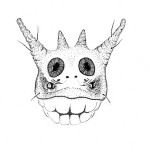

Lots of spiders are soft of hue and hard to tell apart. Not this guy. Jet black with white highlights, built like a car, and often displaying shimmering green jaws. Not huge, but it has a presence: it might be the size of a quarter, legs included. I don’t know if it’s “audacious” because of its bold outfit or its bold habits. Either works. It prowls instead of lurking, so you’re apt to see it walking around in its stop-start manner wherever there might be prey. Two big, soulful, catlike main eyes, like all jumping spiders. At mating time, the males drum and dance and carry on. Don’t we all.