Who you gonna believe, me or your lyin’ eyes?

I like to say I’m self-taught, but at least I’m taught. We’ve all heard that “a little knowledge is a dangerous thing,” but you know what’s worse? A total lack of knowledge. Fear the void. Ignorance is not bliss. It’s fear and confusion.

Writing about spiders is fun! There are always lots of myths, misunderstandings, misreportings, and mirth. There are medical realities unknown even to the well-informed. There are arcane and bizarre biological facts. There are opportunities for pleasant anthropomorphism: Jumping spiders dance and they look like kittens! Baby spiders fly! Since few people know anything at all about spiders, a modest amount of research always digs up new and surprising things.

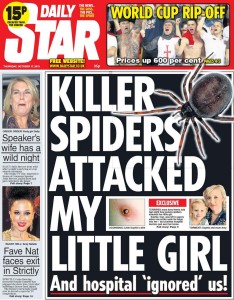

But if the Internet has taught us anything (has it? discuss), it’s that “a modest amount of research” will be not only opposed, but often emotionally and even angrily opposed, by some people who haven’t done any research. Once in a while the arguing doesn’t stray too far from rational turf, even if it’s loud. But in the spider realm, lots of what people say on social media and in news articles takes that weird turn. Stubborn, accusing, insulting. Facts don’t seem to matter. That’s because it’s all about beliefs.

Now I’m in for it. What puts “spider beliefs” in the same category as political, religious, or ideological delusions convictions? I can’t say with authority, having successfully avoided philosophy and psychology for many years. So I’ll just guess.

Years ago, I read everything I could find about urban legends. Folklorist Jan Harold Brunvand (still with us at 90!) was my favorite author. It was great silly fun to see him take colorful stories I’d been told—you were, too—by friends of friends and show them to be just campfire tales. The subtext made this phenomenon even more interesting. People retold those legends, and swore by them, not just for entertainment: they were coded warnings. Urban legends worked their magic when they took something scary and unexplainable—such as a random murder, a ghost story, an uninvited spider—and built it into a tasty, shareable anecdote. And then they told you what to do about it: don’t park in isolated places, do avoid weird strangers, say your prayers, fear nature, tell a friend, trust your gut!

In other words, believe your lyin’ eyes.

The stronger the danger, the stronger the belief. Teenagers who sneak off to dark places really do get murdered now and then. Nature really is out to get you. Cast a skeptical eye upon weird strangers and you might avoid getting robbed or, I don’t know, drugged and dragged into a white van. (Then again, if the weird stranger is actually a hitchhiking Seraph who fingers his flaming sword while he solemnly announces “the Apocalypse is coming” right before vanishing, don’t be skeptical.)

Almost all spiders pose no danger at all in the ordinary run of things, but people never learned that. They’re untaught yet primed to be suspicious. Through a combination of passed-along phobias and an eerily durable sense of disgust provoked by hairiness, legginess, and facelessness, spider anxiety settles into many people’s mindset before they’re even aware of it, and good luck dislodging it. The gut warns us where the brain doesn’t: ignoring the spider menace might bring illness, scars, death!

But even that’s not enough to firm up a spider phobia. Sealing the deal demands an alarming experience; this too is right out of the urban-legends playbook. Either personal (“I was bitten by an invisible spider” or, less often, “I found a spider and it must have bitten me, because what else?”) or very close to personal: “My neighbor’s uncle was bitten by a spider—no, he never saw it, he was just waking up—and somebody identified it as a brown recluse, and he was seriously sick for a long time and are you calling me a liar?”

That last sentence is practically the script for online spider comments. The “somebody” who identified a nonnative (usually invisible) spider is always nonrecoverable. Was it a doctor? Pest control guy? College professor who knows some Latin? Dear old Dad? We’ll never know. That part of the story is lost to time, just like the dead brown spider (if any), but the scary experience lives on.

You know the thing about extraordinary claims. They require extraordinary evidence. And blaming a sore on a spider that you never saw, that doesn’t cause sores, that’s never been seen in your town, and that doesn’t live within a thousand miles of you all sounds pretty extraordinary-claim-y, right? Just as it would be extraordinary if your average Joseph could identify a spider—by species, no less—that he never even saw. That’s not even guesswork. That’s miraculous.

Michael Shermer already has the best book title of this genre: “Why People Believe Weird Things.” It’s worth a read, especially for the way it shows how common, and how human, it is to be fooled. In the case of spiders, we can give this brief answer to Shermer’s title: “Because they’re scary and someone got hurt. By something.” That’s too short for a dissertation (I’ll do better next time, Professor Brunvand) but good enough, I think, for Facebook and Nextdoor.